Originally published on The Manifest Station.

At My Darkest Moment, I Reached Out for Help and Chose To Live

Image by Roy Scott/Getty Images/Ikon Images

Is Mental Illness Having A #MeToo Moment?

Fifteen years ago, I broke up with my very nice boyfriend and plunged headlong into a dark depression. I loved Marc but had known from the beginning that he wasn't the man for me.

I still believe that breaking up was the right move, but I chose a bad time to do it. I was between jobs and felt adrift. I was applying for a more permanent immigration visa (I'm from Canada – and, yes, Canadians need visas too) and it was a stressful and expensive process that made me question my legitimacy. I was on shaky ground emotionally and financially. Marc tried to persuade me to get married to stabilize my citizenship, but I didn't want to. That's how clear I was that the relationship needed to end.

I just didn't realize that by breaking up with him at this unsure moment in my life I was essentially cutting the guy wires of my mental health.

It was a terrifying time, and even today I'm very glad that I came through it alive. I'm often amazed that I feel a basic sense of contentment about my life now. It could easily have been otherwise.

All of this came rushing back to me last Saturday. In the wake of Anthony Bourdain's death the day before, my Facebook feed was flooded with stories from friends and acquaintances expressing their struggles with depression and very close calls with suicide. I had no idea there were so many people like me all around. It felt like the beginnings of a #metoo moment for those of us who have spent time in this frightening landscape. After reading so many stories of people struggling to feel acceptable and worthy, what had seemed like an outlier experience started to seem more ordinary than remarkable. So many of us have #beenthere.

I noticed that the stories in my Facebook feed were from people who had otherwise done well in their lives. They had completed college; they had careers and families; they had traveled. Some of these people I knew outside of Facebook. I would have never guessed how much despair they had lived through.

One acquaintance, Marni Sclaroff, a yoga teacher and mother in Reston, Va., posted a photo of the scars on her wrists where she cut herself for years, starting at age 15. She was also hospitalized. "My depression was existential," she wrote, adding that she came from a supportive family. "I remember, in first grade, struggling to understand what the point was."

Another friend, Ralph De La Rosa, a social worker in Brooklyn, NY, shared that he spent twenty years, from age 8 to 28, thinking of killing himself as a result of early experiences of neglect and bullying.

“No one wants to kill themselves. Ever. They just want the pain to stop.”

-Ralph De La Rosa, social worker

Both Marni and Ralph also shared how they got through these times. Marni wrote that hospitalization and family support helped her, and ultimately she found strength and a sense of purpose in a daily practice of yoga. "It taught me how to inhabit my body, and to love it deeply," she wrote. "It taught me reverence for life, and that we are all connected."

And she wrote, "From my perspective, as someone who has lived through the fire of suicidal depression, I think the way we are going to help people is by normalizing the conversation about it... We need more people who have been through it to speak."

Ralph's turnaround came after he developed a heroin addiction, and a girlfriend kept insisting that he get treatment. At 29 he finally went into rehab where a committed counselor helped him find his way. He got off heroin and stopped wanting to die.

He wrote: "No one wants to kill themselves. Ever. They just want the pain to stop. Feeling heard and receiving compassionate attention can do just that."

When suicide is in the news, instead of expressing sympathy for celebrities we don't know, Ralph suggested that we reach out to the weirdos or seeming outsiders in our immediate circles. Even if their actions at times confuse us, we can try go beyond our comfort zones. Let them know, "I'm here and ready to listen for once, whenever you're ready.'"

I've identified as one of these weirdos for much of my life. I'd always had different aspirations than my working class family. I came to the U.S. by myself without financial help and when I didn't move back to Canada, my family seemed to step back even further.

Even though my friends didn't quite know how to help me through my depression, if it hadn't been for one of them who took me in at a crucial moment, I might not have made it through the breakup alive.

I had already been in therapy for several years at the time. I was smart enough to get treatment for what I thought of as a tendency towards melancholy, but I had stopped taking medication. I hated the label "depressed." I hated the stigma of both my condition and its cure. I had learned, as I became a poet and a writer, that my sensitivity could also be an asset. I didn't want to label it as something to be gotten rid of. But I had no idea how dangerously I was weakening my already delicate support network by refusing medication as I was breaking up with Marc.

I tried to lean on friends. Those who wanted to help — and there were only a few — had no idea how to. "Could you just call me once a day?" I asked, knowing I was asking a lot. For me, contact once in twenty-four hours was still starvation rations, but it was better than the alternative — no contact at all in the many minutes and hours that comprised each long dark day and long dark night.

“Depression talks to you — but it lies to you... What that little voice is telling you to do is not true.”

-Nicole Lewis-Keeber, psychotherapist

One friend called me for two days in a row, then skipped a day, called on the fourth day and then the eighth day. Then the calls stopped. It was clearly too much. It was just too strange, too uncomfortable. And I wasn't getting better.

At my therapist's urging, I went back on antidepressants. But the initial onset of the drugs, which can take three or four weeks to take full effect, made me so anxious I wanted to crawl out of my own skin. One hot Saturday night as I managed to teach my regularly scheduled yoga class, I found myself scratching my arms to keep from having a full-blown panic attack. The idea formed in my addled brain that I should jump off the nearby bridge.

"A lot of mental health conditions speak to you," says Nicole Lewis-Keeber, a psychotherapist and business coach who I interviewed. "OCD talks to you, anxiety talks to you, depression talks to you — but it lies to you. When you're struggling like this, you feel less understood and less able to get help because no one is talking about it. But what that little voice is telling you to do is not true."

After class, I paged my therapist. Under normal circumstances the friendly parting words of my yoga students might have helped me to feel connected and purposeful. This night they did not touch me. I needed serious help. My therapist called fifteen minutes later. He told me if I couldn't wait until our next appointment my only option was to check myself into the nearest hospital.

When I thought of getting on the busy Saturday night subway and checking myself into Bellevue, the public hospital where he worked, I hesitated. I knew what happened in locked wards. Or I thought I did. I'd read many stories of writers who had been admitted to mental health institutions both voluntarily and involuntarily. Sometimes those visits had been necessary but they were never good.

Instead, I called my friend Madeline. Luckily for me, she was home. She had some friends over and they were watching a movie. I should come, she said. I called a car before I could change my mind and follow the call of the bridge. I headed to Queens.

I knew some of the people at Madeline's but by then I also knew that the state I was in would make them uncomfortable. I wanted to hide it. But — luckily again— the movie had started and all I had to do was sit down and watch.

I huddled on the floor, away from the others, hugging my knees to my chest and stared at the screen. I watched with such intensity that I could have burned a hole through the TV. I will never again be able to watch Spirited Away without re-experiencing the physical sensation of fighting for my life. I focused with every cell of my being. I was not going to Bellevue. I was not going to the Williamsburg bridge. I was going to focus with all my might so that the unreasonable and unrelenting thoughts in my head and the jumpy, restless sensations in my body would have to move into the background, even one moment at a time.

“Everyone goes through difficult times. The question is, are they connected enough to get through it?”

-W.S., a suicide hotline worker

It's not just the mentally weak who are at risk for severe depression, as people often think. A perfect storm of experiences can make anyone vulnerable, says W.S., who works at Samaritans, New York City's oldest and largest suicide prevention hotline (NPR agreed to withhold his name for safety concerns). He told me, "Everyone goes through difficult times and multiple problems at the same time, even multiple traumas. The question is, are they connected enough to get the things they need to get through it? Do they have a good support network? People get through difficult times when they are connected."

Life is rarely as straightforward as we would like it to be. While I was depressed, my boyfriend was calling me several times a day, both to check in on me and to convince me not to end our relationship. I tried to stay away from him — I didn't want to break up twice — but I had to admit that his care was helping me. I was desperate for anyone to care, even this person I felt I should let go of. This continued for several months. In that time, the medication kicked in, my mental state stabilized, I landed a great new job — which felt like nothing short of a miracle — and was granted the immigration visa I had applied for.

After another several months, I found the courage to end the relationship without ending my own life. A very new, very different chapter of my life began.

It had required Herculean strength to choose, moment by moment, to live during that dark period. Even after I made it to safety, the experience remained very frightening and also difficult to explain. But it had been burned into me. If you've never been clinically depressed the condition makes no sense. It defies logic. But if you have been, you never forget.

In time, I decided to go off medication, fully aware of the risks and to the dismay of my therapist. I recognize that's not the best choice for many people. But it turned out okay for me. Eventually, I started a meditation practice that has become a profound source of connection and inner stability.

But I also know now that if I'm feeling shaky — as I did writing this essay and recalling that scary time a decade and a half ago — to ask friends, many friends, multiple friends to connect with me, even for a few minutes. I know not to give up until I get the connection I need, and not to be ashamed for asking. Connection can come from anywhere and it makes all the difference. There is nothing worse than suffering in silence and isolation. Not when your very life is at stake. #BeenThere

You Are Not Alone

If you or someone you know may be considering suicide, contact the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255 (En Español: 1-888-628-9454; Deaf and Hard of Hearing: 1-800-799-4889) or the Crisis Text Line by texting 741741.

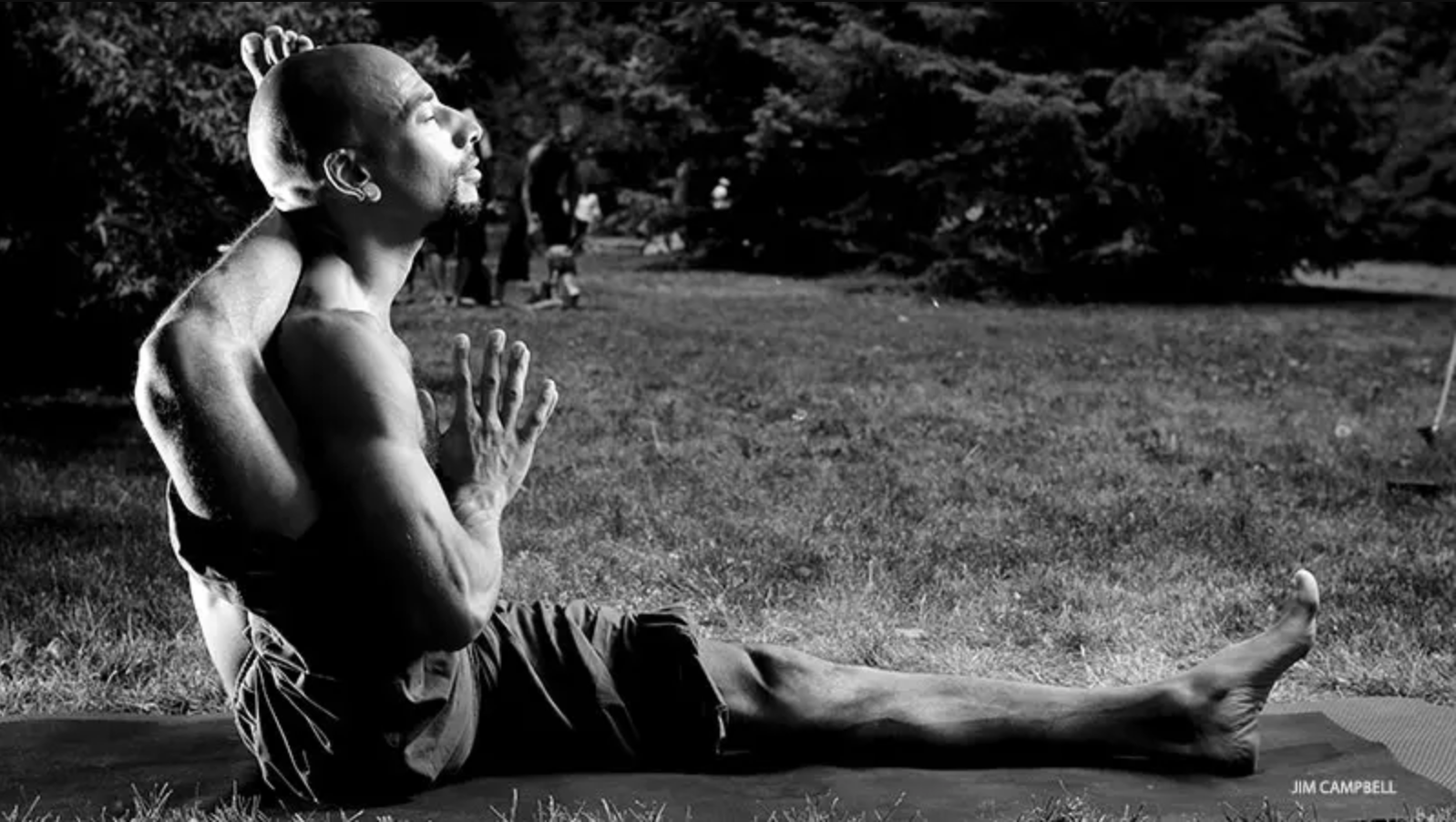

Teacher Spotlight: Terence Ollivierra on Rolfing + Yoga

This teacher in Washington, DC, integrates Rolfing with yoga to help his students move more freely.

With his history of weightlifting, Terence Ollivierra had a tendency to overdo yoga poses, which led to thigh and hip pain. He found no relief from acupuncture or chiropractic therapy, and while he sought balance through his yoga practice, the process was slow, the discomfort worsening. Then, in 2005, an Iyengar Yoga teacher introduced Ollivierra to Rolfing, the hands-on bodywork designed to release tight fascia (connective tissue) so that the body can realign itself. Rolfing—combined with an integrative yoga practice—proved to be the solution. Ollivierra went on to complete his Iyengar Yoga teacher certification with John Schumacher in 2009, and trained to be a Rolfing/Structural Integration body worker so that he could better serve his yoga students. Today, Ollivierra is a perceptive teacher who aims to help students identify and modify movement patterns that cause them pain.

How does your Rolfing training inform your yoga teaching?

I have become much more sensitive to the subtle causes of major imbalances in people’s physical structures. Before a student tells me about an injury, I have already noticed how she stands and walks and have a good idea of issues she’s facing—and where to begin looking for solutions. For example, someone’s back may feel good in a particular yoga pose, such as a backbend, but her alignment could create an issue if she’s only moving from her lower back. She may feel a “release” while in the pose that might give temporary relief, yet she has problems later because a pattern of poorly performed asana is being repeated again and again.

What do you love most about your yoga students?

Their humility. The fact that they show up is humility. I am a relentless teacher. The purpose of a class is to experience another perspective on how this work can be done. I don’t let people rest in their habits. You have to be present or else you’ll get called out.

What is your practice like?

Most of my practice is Savasana and breathing, such as yoga nidra, the “yoga sleep” meditation in Savasana. I used to do a minimum of three hours of asana a day, not counting breathwork and meditation. Now I do just a few poses—they change depending on the day and my needs—beginning and ending with Savasana (with knees bent at 90 degrees, feet fist-distance apart, elbows wide with palms down or hands on the belly). It takes an hour or two at most because, after all my training, I’m sensitive to my own structure and its movements. And I’m not one to do things halfway.

In the Details: Ollivierra shares a few more of his favorite things.

Movie: I’m a Star Wars geek. I often fall into a Yoda voice while teaching. I’ll say, “Do or do not—there is no try!”

Music: I play electric bass and fool around on guitar and keyboard as well as double Native American flute and the hulusi, a Chinese flute.

TV Show: Avatar: The Last Airbender. This cartoon is deep, full of wisdom, and will leave you feeling good all around.

Signature Dish: Coconut curry lentils. I’ll add in kale, butternut squash, and sweet potato.

Books : Eknath Easwaran’s translation of the Bhagavad Gita, and Eckhart Tolle’s The Power of Now.

Rock Out with Teacher Mary Clare Sweet (+ Get Her Playlist)

A Nebraska-based yogini finds her groove bringing rock ‘n’ roll to yoga.

A Nebraska-based yogini finds her groove bringing rock ‘n’ roll to yoga.

From a musical family (her uncle is Matthew Sweet), Mary Clare Sweet followed her passion for rhythm and dance to New York City, where she became a student of the venerable Sri Dharma Mittra, founder of the Dharma Yoga Center. From there, Sweet’s yoga career has taken off. At age 26, she opened her first vinyasa studio in Omaha, Nebraska: Lotus House of Yoga. Five years later, she is the owner of five Lotus House locations and a regular teacher at yoga festivals nationwide.

What does your practice look like?

My day starts with meditation and breathwork. It’s not easy, since I want to check my phone first thing when I get up, but I try to resist, sitting for about 10 minutes and then doing Kundalini exercises, including the Ego Eradicator. In total, I try to practice yoga for an hour a day. Some days, I’ll just let my body move, like when I was a ballet and jazz dancer.

How were you introduced to yoga?

When I was growing up, my mom practiced in a basement studio with tapestries on the walls. And I grew up dancing around the house with my parents and rock-musician uncle. There was always a token yoga class at dance camp. But it wasn’t until I moved to New York City and met Dharma Mittra that I thought, ‘This is what I want to feel all the time’—the way I felt when I looked into his eyes and saw the spark inside his heart. There was undeniable compassion.

Music is big for you and for Lotus House of Yoga. How is it incorporated into your classes?

Making a yoga playlist requires intention. I base mine on the chakras, starting with grounding music that brings you into the moment. Then I move into rhythmic sounds that you can feel around the second [svadhisthana] chakra. Next, I bring in music that is fiery for the third [manipura] chakra. For the heart chakra, I use music that helps students tap into collective consciousness. Near the end of class, the songs get more poetic to help students center on self-expression and the fifth [visuddha] chakra. In the final moments, I want angelic sounds that can activate the third eye and crown chakra. I’m looking for vibrations that dissolve your ego.

Sweet shares a few more of her favorite things:

Pose: Navasana [Boat Pose] lights a fire in me to speak my truth—to say what I mean and mean what I say—without feeling afraid.

Song: “You Make Loving Fun,” by Fleetwood Mac. It reminds me not to take things too seriously.

Practice Space: I feel safe and stable at my mom’s house and dad’s house. There’s a root-chakra energy there; this is where I came from.

Food : I eat seaweed in everything: seaweed salads, wraps, sushi. It offers phytonutrients; it’s salty, savory, and so versatile.

Color: Since I was a little girl, yellow has been my favorite color. It means life, sustenance, growth, sunshine, and courage.

Practice to Mary Clare Sweet's Yoga Playlist

Former NFL Linebacker Keith Mitchell's Mindfulness Mission

How former NFL player Keith Mitchell found healing through yoga and mindfulness. Now, he wants to share that experience with others.

A spinal injury ended Keith Mitchell's football career in the NFL, but it also led him to find healing through yoga and mindfulness. Now, he wants to share that with others.

When a midgame spinal injury rendered NFL linebacker Keith Mitchell immobile in 2003, a physical therapist introduced him to the concept of conscious breathing to bring more oxygen to his partially paralyzed body. He started to notice changes, mentally and physically, and six months after his fateful tackle, Mitchell could move again. Within a year and a half, he was practicing asana.

Yoga Breathing + Meditation for Injury Recovery

Today, he credits breathwork and the study and practice of yoga and meditation with his ongoing recovery. And while he still battles fatigue, anxiety, and migraines, Mitchell no longer dreams of a return to a football career. Instead, he now dedicates his time and energy to teaching veterans, athletes, kids, and families who may not otherwise have exposure to mind-body practices.

“Yoga and meditation help build a relationship with the Self,” Mitchell says. “They help us listen to ourselves and unlock the intelligence of the body.”

As part of his mission, on January 31, Mitchell will host a landmark yoga and meditation event and 5K run and walk at the LA Coliseum, called the Mindful Living Health Expo and AltaMed 5K. “We want to get 10,000 people on their mats,” Mitchell says. “Yoga and mindfulness are not just for yoga people. They’re for everyone.”

How to Fail Up: 5 Steps to Cope with (and Conquer) Failure

It was a powerful moment when a teary-eyed David Damberger of Engineers Without Borders admitted from the TEDx conference stage in Calgary, Alberta, that the nonprofit project he’d been working on for five years to bring clean water to poor villages in India had failed. Yet as hard as it was for him to publicly announce defeat, it triggered a critical realization for…

Meet Yoga Teacher Dana Walters

This vinyasa teacher's nonprofit brings yoga to the people of Richmond, VA. Here's the scoop on her practice.

After a friend’s death five years ago, Dana Walters manifested her late friend’s dream by co-founding Project Yoga Richmond. Walters studied with yoga greats including Rolf Gates, Noah Levine, Judith Lasater, Nikki Myers, Kathryn Budig, and Seane Corn, and she keeps her practice mindful and steady. She offers the project’s donation-based classes to people who couldn’t otherwise afford them. Yoga for all? That’s a mantra worth repeating.

Yoga Journal: You were called an agent of positive community change by Style Weekly. Why?

Dana Walters: Probably because I caught their eye through Project Yoga Richmond, which I launched with five friends. We offer donation-based studio classes, plus free and low-cost yoga to children with autism, adults with developmental challenges, youth in juvenile-detention facilities, people in addiction recovery, seniors, and teens in city schools. We roll out about 1,300 mats each month through our classes.

YJ: What’s a key takeaway from your practice?

DW: I used to have a more-is-more mentality: If a twist feels good, more twist must feel a lot better. But I learned that just because you can move deeper doesn’t mean you should in that moment. Now I teach that more is sometimes fun, but not necessarily the best choice every time.

YJ: What’s your favorite yoga pose?

DW: Up Dog. Typically, it’s a transitional pose, but I pause in it. It’s super grounding, requires core strength and inner consciousness, and requires me to open up and soften.

YJ: What moved you from being merely interested in yoga to being passionate about yoga?

DW: That tipping point came when I shifted from teaching poses to teaching people. I credit Rolf Gates for that. He showed me that an understanding of and balance within the chakras ultimately informs how we are in the world. That was a powerful teaching. So now I try to encourage individual inquiry. I try to help others learn that knowing the poses is merely a path toward knowing themselves.

5 More of Dana's Favorite Things:

Snack

I pop the top off an avocado, take out the pit, add a bit of sea salt, and scoop it out like ice cream.

Color

Our front door at home is turquoise. My mat is turquoise. My watch is, too.

Musician

Elena Brower told me about Garth Stevenson. For class, his music is both grounding and soaring.

Pets

I have three senior rescue dogs: two poodles and a Maltese. They remind me to breathe.

Escape

Running or walking on the eight-plus miles of Richmond’s city trails that surround the James River.

Easy Seat: How to Sit With Less Pain: Book Review

AS PUBLISHED IN YOGA JOURNAL

Given how ubiquitous hatha yoga is today, it might be surprising to learn that just a few decades ago it was frowned upon by many Buddhist practitioners. In his forward to Jean Erlbaum’s well-informed book Sit With Less Pain: Gentle Yoga for Meditators and Everyone Else, Buddhist teacher Frank Jude Boccio confesses that at one time he did postures secretively at Buddhist retreats, afraid to be chastised for stretching his body between long sits.

Today, it’s clear that asana has many benefits, among them preparing practitioners’ bodies for meditation. Yet we haven’t seen an onslaught of books like Erlbaum’s that can help us learn to sit in contemplative practice longer while also showing us how simple yoga movements can ease tightness from routine tasks like sitting at a desk all day.

Erlbaum’s presentation is straightforward and clear, with just enough detail for non-experts to understand how to do the simple poses she outlines. She helpfully categorizes the offerings into upper body, mid-body, and lower body. Chair-based postures are included for those whose lack of mobility limits them from getting up and down from the floor.

In the least, Erlbaum’s gentle stretches and well-designed sequences can help people with chronic pain, stiffness, or a limited range of motion. At most, hatha yogis who do her suggested poses mindfully over time will understand how to cultivate their asana practice to establish a lasting easy seat.

AS PUBLISHED IN YOGA JOURNAL

Sacred Sound: Book Review

AS PUBLISHED IN YOGA JOURNAL

Seeing that contemporary yogis and yoginis have had no single source to explain the meanings of popular mantras or kirtan chants, Alanna Kaivalya has stepped in with Sacred Sounds: Discovering the Myth and meaning of Mantra and Kirtan. The book, divided into two sections—one covering 11 mantras and one 10 kirtan chants--devotes a chapter to each, explaining its significance, its governing deity and associated myths (if any), as well as giving suggestions for practice. No doubt you’ve already heard many of these—such as Om Namah Shivaya and the beloved and ubiquitous Om—either chanted in class or as a part of your class soundtrack. If you’ve ever wondered what they really mean, this book will begin to light the way.

Kaivalya, who is a touring kirtan musician herself, encourages practitioners to try mantras or participate in the uplifting group call-and-response of kirtan as a part of their regular yoga practice. In fact, her intention is to make what may seem like more esoteric parts of yoga more approachable to everyone, spreading the higher vibrations they inherently embody. While it’s not traditional—or in some cases, safe—for mantras to be practiced, as Kaivalya says, “in any way you like,” the ones she presents here will do no harm. For certain, the explanations of the Sanskrit and the myths help provide deeper context to the sounds—whether you are chanting the, or listening in—making kirtan an accessible way to attune to the joyful divine. So go forth, yogis, and sing!

AS PUBLISHED IN YOGA JOURNAL

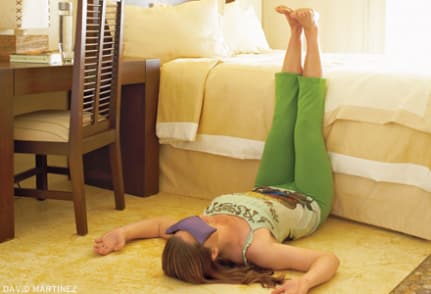

7 Ways to Create A Yoga Staycation

AS PUBLISHED IN YOGA JOURNAL

Feeling frazzled and in need of a yoga retreat—but an exotic getaway is not in the budget? Here’s how to design your own thrifty yoga staycation.

Clear Your Schedule

Plan a weekend and preferably 3-4 days for your at-home retreat, and clear your schedule of other commitments, just as if you were leaving town. “Taking a day or two out of your usual routine to commit yourself to a practice can help give you per- mission to be where you are, instead of worrying about where you’re going,” says Dana Courtney, creator of affordable weekend yoga “urban retreats” in Manhattan, Brooklyn, and New Jersey.

Practice Morning and Night

Buy a class card or pass from a local studio, and choose two classes to take each day. If you prefer practicing at home, dedicate two sessions to your practice: an hour in the morning and an hour in the afternoon. “Practicing twice a day ultimately takes you deeper into your practice,” says Kino Macgregor, founder and owner of Miami Life center. “If you have one really active practice in the morning, then you can be more meditative and introspective in the afternoon, working on alignment and therapeutics. It creates a holistic program.”

Get a Cooking Buddy

Have a friend join you, and share the shopping and prep for a weekend of healthful, simple-to-prepare meals, drinks, and snacks.

Tune In

In between your yoga sessions, read, meditate, draw, write, take naps, or do other restorative activities. If you’re not a regular meditator, or just want to try something new, check out these techniques and audio practices.

Treat Yourself

Make time for at-home spa treatments, too, like a steam facial or a foot massage. Click herefor tips on maintaining healthy, lustrous skin.

Unplug

Switch off your phone, resist checking your email, keep online time brief, and get outside! Levi Felix, co-founder of Digital Detox, says, “When we disconnect from devices, we reconnect to ourselves, to nature, culture, and the community around us. The data shows the health benefits of unplugging: It lowers blood pressure, lowers heart rate, lowers cortisol, and helps us sleep better.”

Early to Bed

Plan to get sufficient rest, at least 7 hours a night, so that you’re truly refreshed when you emerge from your home retreat.

Pick Your Practice: Exploring and Understanding Different Styles of Yoga: Book Review

AS PUBLISHED IN YOGA JOURNAL

Grown out of a Master’s thesis in professional writing from USC, Pick Your Practice: Exploring and Understanding Different Styles of Yoga, is 500-ERYT instructor Meagan McCrary’s helpful guide to 17 styles of yoga as currently practiced in the US today. The book starts with three foundational chapter—“Yoga Explained,” “America’s Yoga History,” and “Philosophical Foundations”—before diving into the nuts and bolts of Ashtanga-vinysasa, Iyengar, Bikram, Jivamukti and three other widely practiced American yoga styles. Ten more schools—perhaps considered specialty styles—such as Viniyoga, Anusara Yoga, and Forrest Yoga are overviewed in one further chapter.

Methodical and thorough, this book will be especially helpful to the advanced beginner who has practiced enough to want to branch out, but does not yet know what her options are. The book sheds light on the founders of each yoga style, the early days of the practice, as well as what’s distinctive about a particular approach and how it’s typically sequenced. Boxed call-outs showcase interesting factoids and key bits of history of philosophy.

It’s not always clear what criteria McCrary used to prioritize styles—why confine the ubiquitous vinyasa style, for example, to a mere side-note of Ashtanga yoga, or privilege the somewhat passé Integral yoga in the same breath as Iyengar? But it is apparent that McCrary made a good-faith effort to research schools extensively. At root her even-handed presentation acknowledges that no matter how different American yoga styles are, they are joined by one purpose: to help people attain a degree of self-awareness that comes only from devoted practice.

AS PUBLISHED IN YOGA JOURNAL

Brenda Feuerstein Keeps Traditional Yoga Studies Going

While Finishing Her Own Important Work

Georg Feuerstein, the widely respected Indologist, originally from Germany, authored and edited over 50 texts of Yoga philosophy and practice. Titles include The Deeper Dimension of Yoga (2003), The Yoga Tradition (2001), Encyclopedic Dictionary of Yoga (1990), and even Yoga for Dummies (1999), co-authored with Larry Payne.

In 1996, he established the Yoga and Reseach Education Center in California, which he ran for 18 years until he moved to southern Saskatchewan with his Canadian wife, Brenda, in 2004. Feuerstein died on August 25, 2012, from complications as a result of diabetes.

Brenda Feuerstein continues the legacy of her husband’s research, taking their Traditional Yoga Studieswork more into the public eye with her teaching and workshops. YogaCity NYC's Joelle Hann spoke to her in her home in Saskatchewan.

Joelle Hann: I know you just passed the 1-year anniversary of Georg’s passing on August 25th. With your research and teaching lives so intertwined, how has the past year been for you?

Brenda Feuerstein: I made conscious decision to write openly about my process of grief so that there was a possibility for others to heal from my raw moments, or the moments filled with joy and memories. I’ve had so many emails thanking me for doing that. It seems to have allowed others can grieve in their own way, too.

JH: It looks like you have a number of new things in the works to help keep Georg’s work alive and to expand the reach of the classes he offered.

BF: After Georg passed, I needed to decide how to move forward. At first, I wanted to go deeper into spiritual practice but after a few months I realized I could also do that by engaging others. In August, I lead the first retreat, gave my first public talk. It’s about being on the right path with the right people at the right time.

JH: Can you tell me about what’s developing at Traditional Yoga Studies?

BF: I’m heavily into working on a course on Tantra – so that people can learn the diversity of it. I’m not approaching it from a neo-Tantra perspective, of course [Ed: neo-Tantra is a contemporary Western movement that focuses on sexuality]. That’s on hold until I have more people on board to help. It will be popular and “big” course. But I’m hopeful that in the next year I will be collaborating with people I greatly respect as well as people who are up and coming.

JH: Can you explain what the Memorial Fund is?

BF: The Georg Feuerstein Memorial Fund is an umbrella name for several projects, the most important of which is a free distance learning course for people who are incarcerated. It will also be available to inmates’ families and prison staff.

I’m getting together a team that’s keen to work on programs of personal transformation—James Cox, for example, comes with many years of experience in prison yoga and has agreed to be on our board of advisors.

The program includes meditation, lots of questions to reflect upon, and journaling. Tutors act as a sounding board to ask additional questions or hold space for students, recommend books, audio, or visuals to get a deeper level of transformation.

We also have a project that’s working with people in addiction recovery, and a youth project that is in development stage and will be launched in 2014. I’m currently working with advisory board to build this project. We will offer skills to help youth better understand and develop creative lifelong ‘marriages’--of family life and community through the teachings of yoga.

I wanted to figure out how to work with people who don’t have the freedom to leave a facility, to help them find inner freedom within a facility. I also wanted to bring something to youth so that they would not end up in facilities.

JH: And you have an advantage there because Traditional Yoga Studies has always offered online courses, right?

BF: We started in early 2003 when nothing was really happening in long distance learning courses. The material doesn’t lend itself to short courses—the “History, Literature, and Philosophy of Yoga” is 800 hours for example. But the tradition is rich and expansive so there’s no way not to give huge amount of material.

As Georg’s health deteriorated, increasingly my role was to serve him and create a lifestyle where we could practice and enjoy each other while we could. He encouraged me to take over the teaching. Essentially Georg and I ran this whole organization as a 2-person show, all the administration and marketing, advertising, teaching, public speaking, and course development.

JH: You are coming to New York soon to try to meet with the Dalai Lama and continue your course in the Contemplative End-of-Life Care program. Will you be giving any workshops?

BF: I made the decision that this trip needs to be about service to people in great need. So, after my 9-day retreat for the Contemplative End-of-Life Care program I will be heading to the streets in various parts of New York State. I will be holding space for homeless people facing death alone and helping bring yoga and meditation to more at risk youth and adults. It’s my Dying with Love Pilgrimage.

Hip-Hop Yoga In South Jamaica, Queens

When I call Erica Ford she has almost has no time to talk. She and her team of volunteer peacekeepers in South Jamaica, Queens, were hustling to stop a retaliation killing after a 14-year-old girl was shot over the weekend while riding the Q6 city bus.

Life in the Straw Village: Basic Luxury in Kajuraho, India

AS PUBLISHED IN YOGA NATION

You Really Can Get Attached to Anything

It’s been an interesting process of getting used to living outside in India.

The huts are exactly the same

“Living” means: sleeping, changing, writing, reading, resting, bathing, and answering nature’s calls IN STRAW HUTS. We have real flush toilets (as opposed to squat toilets), buckets for “showering,” and outside sinks (which makes for chilly teeth brushing in the pre-dawn hours when we stumble off to meditation).

There was never any soap at the sinks

“Outside” means: we have the illusion of privacy as well as some real shelter. That illusion is worth a lot.

But the huts are not warm. And many leak. We’ve had several loud and violent storms to test out their waterproofness—and mudproofness and damproofness. I’d give them about 50/50.

Inside our straw castles. Four to a hut! Mosquito nets strung between bamboo poles; industrial green carpet (over straw over mud) keeps out the worst of the damp.

You know a lot about your “eco hut”—and yourself— after two days of torrential rain in an area that is not supposed to have rain as the clay earth sluices down the paths and makes a mud dam in front of your hut.

A strip of yellow silk in the doorway brightens up our huts

And the huts definitely do not protect us from the sounds of neighbors. Who knew that SO many people snore so loudly?

For us middle class Westerners, this way of living is a practice of austerity.

But as we’ve been reminded, for locals in Allahabad and Kajuraho, the way we are living is luxurious.

Toilets and showers

I will admit that this is a step up from tent camping. I am writing this from inside my hut, for example, sitting at a metal table with a blue plastic tablecloth stretched over it. We have metal cots off the ground, and clothes lines, plus lawn-green carpeting to protect us from mud and dust.

And one thing I know: I can get attached to anything. Anything at all.

I got attached to the readily available WiFi in Kajuraho. Even the cold, cold nights, bathing outside from a bucket was bearable if I had WiFi to make Facebook updates and write blog entries (only slightly kidding).

You haul in hot water with one bucket, mix it with cold from the spigot, then pour over you with the cup provided. Bucket bath!

That disappeared in Kajuraho. But the bucket baths and cold temperatures remained. Wah-wa.

In Kajuraho, I got attached to hut 7 where I weathered the interminable storms. Hut 7 almost flooded in the mud sluice, was crowded with 2 women from Duluth, another from Chicago, and me. It was damp and damp and damp. And damp. Then musty. My bed was both sloped downwards and tilted to the side like a permanent Tilt-a-Whirl.

Bucket bath set up–close up. Basic, basic, basic.

And yet I felt anxiety when I had to move into hut 49.

(Now the question is: what do I care whether I’m in straw hut 7 or straw hut 49?! They are exactly the same, just positioned slightly differently towards the bathrooms. Still I got fixated for a few hours on how much worse hut 49 was going to be. I had established my patterns and I didn’t want to budge. This is the stuff I came to India to deal with?!?! Answer: yes.)

But after two or three days in hut 49, I had completely forgotten about the charms of hut 7.

So it goes.

Campus gets pretty after torrential rains

Most of us have gotten comfortable with this quasi-camping set up.

Temperatures are getting warmer now and days are brighter. I don’t have to wear every single piece of clothing I brought to India when I go to bed. I don’t have to wait for a warm patch in the day to bathe (or just skip it for a few days until bathing is urgent).

I don’t mind doing laundry by hand. And every time I shower now, I’m sure to wash some undies. Life has become easier.

72-yr-old Sylvia does laundry by hand at the hot-water station

And there are some surprise boons. After all that rain, the desert campus has sprung into bloom. Ceramic pots of marigolds, cosmos, and asters line the paths and decorate the huts. The trees are sparkling green.

Birds have arrived in abundance: green parrots, eagles, sparrows, a large swallow-like bird, peacocks, neelkanth, and many many others that sing and chirp and whir. In fact, a pair of sparrows just flew into my hut!

After the rain

At night the jackals howl their mysteriously poignant songs arching back and forth across the hills. The farmers answer them with their ghostly shrieks meant to scare away nilgai—the large antelope/deer/horse-like creature that tramples crops (the male is actually blue colored).

Himalayan Institute campus, Kajuraho

Most of us have forgotten our discomfort in the straw village, our Western privileges, proving that you really can get used to anything.

Even basic luxury can be luxurious.

Sherry, Sylvia and I go into town for lunch–breaking out!

And now some people don’t want to go back to their easy showers and toilets, central heating and A/C.

You really can get attached to anything.

Kunda (fire pit) at the special banyan tree

AS PUBLISHED IN YOGA NATION

Carnival on the Ganga: The Kumbha Mela by Night

Allahabad, India

AS PUBLISHED ON YOGA NATION

The night before the massive influx of pilgrims to the Kumbha Mela, a massive, pop-up spiritual congregation in Allahabad, India, Ali, Stewart, Cathy and I snuck off the Himalayan Institute campus. February 10th was going to be an “auspicious bathing day”—a very special day to take a dip in the Ganges—under a new moon, a time to let go of the past—habits, events, troubles—and inaugurate new beginnings. We wanted to see it up close, for ourselves.

In fact, ten MILLION people were expected. One million were already on site. We wanted to go into the Kumba at night, to see a different Mela.

We wanted to go before the swelling masses became impassable. Not to mention potentially hazardous. (post script: one of the makeshift pontoon bridges across the Ganges collapsed, and some pilgrims did die…)

We also wanted to escape what has come to feel like a very pleasant and highly scheduled summer camp on the H.I. Allahabad campus.

Why not? says Ali

We set off at 5pm aftert signing out at the Himalayan Institute’s main gate, knowing that we would miss dinner. We walked the mile up the Ganges over uneven goat paths and piles of trash.

For the first time, my feet did not hurt in spite of my blisters. It was exciting to be out of the herd. We reached the first and second gates into the Mela in a buoyant mood.

First gates — advertising for holy men is everywhere

We didn’t have to go far to encounter something spectacular: a steady line of pilgrims coming across the first bridge. They were hunched under bags of bedding striving forward with their walking sticks.

It was sunset, and the sight of all those scarved heads and sandaled feet crossing the river at dusk with such purpose was pretty impressive.

It gave us all a deep feeling for the importance of the pilgrimage, the scale of it in people’s lives. There’s no way that other huge festivals—such as Burning Man or Brazil’s Carnaval—could have such a massive feeling of sweet purpose.

Setting sun illuminates pilgrims

Past the second gate and down a side road we entered the main grounds of the Mela. People were walking, bathing, attending talks, but most were cooking over wood fires.

Those who weren’t already encamped in a tent camp, simply slept bundled up person to person on the side of the road. The sheer number of people was astounding, and the vibe—so different from a few days before, in the afternoon—was of purposeful excitement.

The air was burning with smoke

We walked pretty easily through the masses of people streaming past us, no jostling, no harassment, except for the very gentle delight of every single Indian (it seemed) to have their photos taken. Or to take photos of us, the impossibly light skinned people.

“Single photo! Single photo!” shrieked the children we passed, waving madly at us. “Tata! Tata!” (tata = goodbye)

Walking through swarms of pilgrims

We didn’t go into any of the makeshift palaces that lit up the main streets like Las Vegas, but we window-shopped.

In one, an allegorical play was underway (we understood nothing, but the costumes were fab).

In another much more modest one, a man with long wooden earrings was dancing a very feminine dance on a stage lined with male musicians.

KM spectacles

In yet another, a group of very pale Westerners sat around a ceremonial fire (kund) with zombie expressions on their faces throwing offerings of herbs and flowers into the flames. We looked, but we didn’t taste.

Ali was eager for snacks since we’d missed dinner back on campus. Truth be told, we were eating so much (3 very good meals a day) that I was not hungry at all.

But the snack stand was interesting. Ali bought dried and spiced chick-pea sticks mixed with dried peas, served in little cones of Indian newspaper. Yummy.

Night snacks

Finally, our eyes were streaming from the fire smoke and the wandering around began to be painful. We were coughing and a wee bit concerned to get back to campus not too late after our agreed-on time.

For a disorienting 1o minutes we argued about directions and took a few wrong turns (to some dark and smelly corners of the Mela)—but then Stewart expertly guided us back to the road we needed.

We arrived back—smokey and tired, but exhilerated—just before 10pm. And it seemed that back in the Mela many of the more energetic and vocal camps were just getting their kirtans started.

The chanting, singing, preaching, and “swa-ha”s went on all night, as usual. They were loud and fervent and clashing and wonderfully chaotic.

Ah, KM, so much to offer, so hard to decipher.

Sunset downstream from the Mela

AS PUBLISHED ON YOGA NATION

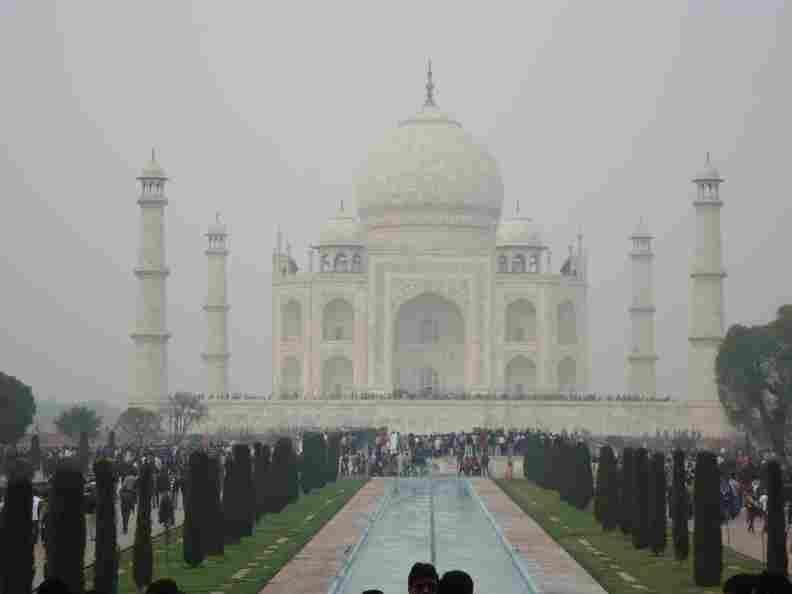

In the Beginning, I am a Tourist

AS PUBLISHED IN YOGA NATION

Gateway to the Taj Mahal

was a 23 hour journey from Newark, NJ to Agra, India (13 hour flight, 4 hour wait at the Delhi airport to join my group, agonizingly slow bus ride through the “fog”). Left Feb 1 and arrived Feb 3. Feb 2 just disappeared.

Taj Mahal

Here are a few photos from initial landing in India. Fleeting first impressions.

Spent a blurry Sunday afternoon at the Taj Mahal. Glad to see that the Indian tourists outnumbered the Westerners.

Sunday pilgrims to Taj Mahal

The Taj Mahal, a mausoleum to a Muslim king’s favorite wife, sits on the Yamuna River which is perpetually misty.

Loving the mesmerizing colors of women’s saris.

Great color

We were taken to a carpet maker in Agra. Beautiful, hand-knotted silk and wool carpets. Then out came the chai and the hard-soft sell.

Hand-knotted carpets

And that was about enough sight-seeing for me. The next day, a 10-hour bus ride to Allahabad, where we are now. Slowly getting introduced to the Kumbha Mela.

Now that the travel is over, the journey begins.

AS PUBLISHED IN YOGA NATION

Flowing with the Kumbha Mela

AS PUBLISHED IN YOGA NATION

I always understood that I was coming on a pilgrimage when I signed up to come to the 2013 Kumbha Mela in Allahabad, India. I just didn’t know what part of this trip was going to be pilgrimage. Or even, perhaps, what a pilgrimage was.

On the road to the Kumbha Mela

I fantasized about meeting holy teachers who had descended from their reclusive, Himalayan caves—I had read about this in a newspaper article.

I dreamed of unexpected—but very enlightening—encounters with humanity on the dusty road to the great festival: After all, Parahamsa Yogananda famously met an incarnation of his teacher’s teacher at a Kumbha Mela in the early 20th century.

At the very least, I thought, the Himalayan Institute in Allahabad would invite some sages with whom they had personal connections to the campus for talks and maybe blessings, too. This was a long-awaited spiritual gathering of up to 100 million people, and I was traveling from so far away, after so much preparation—something had to happen.

On the road

I’ve been in Allahabad for 2 1/2 days now. On the first day, we were hauled (literally) up the Ganges on wooden boats til we reached the most auspicious place, the confluence of the Ganges and Yamuna rivers, as well as the mysterious Saraswati river that you can’t actually locate on any map.

Small, strong men rowed, punted (with long bamboo poles), and pulled us with string. The boat traveled against the current, under makeshift pontoon bridges, dodging garbage and sand bars, until we reached the sangam, the meeting of the waters. There, we blessed ourselves by scooping up handfuls of the highly toxic river (E.coli levels at 100x what’s acceptable), saying a prayer, then sprinkling the auspiscious water over our heads—and liberally dousing with hand sanitizer afterwards.

It seemed like cruel labor for the men until we were informed that their previous cargo had been SAND (sand from the Ganges is highly prized by cement factories).

Still, nothing happened. But no worries, I thought, tomorrow we are going into the Kumbha Mela for real, finally reaching a destination that I have been thinking about for 3 years. With 8 square miles and countless sadhusprominently dressed in orange robes, something was bound to happen.

I set out with Stewart, my new Glaswegian friend. We were so deep in conversation about the pilgrimage itself that we hardly noticed the piles of fine white sand that our feet were kicking up. Soon our mouths were full of sand, and any exposed skin slathering in sunscreen was covered, too. I noticed local women were holding the ends of their saris over their mouths.

Kumbha Mela road is dusty, muddy, and hot

It was the tremendous noise that stopped our conversation. Singers, chanters, proclaimers and lecturers projected at top volume through cheap loudspeakers. Meanwhile rickshaws, motorcyles, bicycles, and Mercedes Benz jeeps (full of sadhus in orange robes) honked and whistled and rang on either side of us. We couldn’t hear anything else.

We caught up with other people from the Himalayan Institute at a fork in the road: now we would go down into the mele, and maybe cross a pontoon bridge to the Kumbha Mela grounds on the other side of the Ganges.

Anyway, anyhow

We added Ali and Mangesh from London, also Selina an English nurse transplanted to America to our two-some, and together headed down towards the sangam, the confluence. This time from the land.

Along the way, we browsed bangle shops, haggled for malas (since Mangesh speaks Hindi), took photos and generally wondered what was going on inside all the tent camps that lined the makeshift road. That’s where, supposedly, the sages held court.

Often, as we took our pictures, a small crowd would gather to take photos of us. It seemed fair, although it was weird. Or a sage would stop and, with a kindly expression, stand a little too close and stare at us with unblinking eyes.

A baba

After a packed lunch of potato chips, pakoras, and (fake) mango juice-boxes we visited the bathing areas that faced the sangam. Here, whole families and villages were bathing in the holy river, the Ma Ganga. Selina was excited to immerse herself, but I wasn’t interested in getting closer to the bacteria.

Bathing in the Ganges

Mangesh did buy a boat of flowers and sent it out into the waters. (It flowed right back in, and Ali made fun of him.)

Flower boats

And then we had to admit that we were hot, still hungry, tired, and ready to go back to the campus. Which seemed a long ways away at that point. We were done and we still hadn’t really encountered that thing that was supposed to happen.

We were just tourists wandering in a fair ground, surrounded by thousands of people elaborately wrapped in gorgeous colors, or lining the roads trying desperately to eke out a living.

Entrance to a sadhu’s tent camp

The language barrier made it so that we would never really understand whose tent camp we were passing, which ones to go in, and which ones to avoid. They all looked as if they could swallow us up whole, exotic as we were with our very pale skin. Even Mangesh, who is Indian, couldn’t understand what we were seeing.

Tired from the dust, the noise, the heat, and the more-or-less aimless wandering in search of the fulfillment of Our Pilgrimage, we turned back.

“Are you feeling the auspicious energy, or anything?” asked Ali, former IT guy for a London investment bank.

“Not really,” I said. “I mostly feel tired.”

There were some silent, tired nods around our little group.

At last, we picked a tent camp at random and stopped in. The less digestively-challenged of us accepted the free meal being offered, sitting back to back on the ground with Indian pilgrims who presumably did know why they were here and what they were supposed to be doing.

On the way back, I suggested a rickshaw. Mangesh haggled a price and we dove in—Selina, Ali, Mangesh and me. We picked up Stewart who had booked it on ahead of us. He looked very pleased when we pulled up.

Stewart and Ali in the rickshaw

“The Ganges is inside you,” said a senior Himalayan Institute teacher. “Don’t get caught up in whether you immerse yourself or not. Notice her qualities, how the river flows, how constant and abundant she is. This is what you want to connect to. The vitality, the power.”

“There are so many political factions at the Kumbha Mela,” said another teacher later over chai, “And in India politics and religions are completely mixed together, no separation. There are serious lobbyists working the Kumbha Mela. It’s all over our heads. Sure, there are some very accomplished holy teachers in there, but the chances of us figuring out who’s who are slim. Even so, we’re all here at an auspicious time, doing our own practice, and that’s the benefit. The Mela is not the benefit, it’s your own practice.”

The rickshaw ride back was wonderful. Back on campus, we bathed from buckets in straw huts equipped with clean water. I didn’t care how simple it was—the water, the quiet, and the afternoon breeze felt as “authentic” and “auspicious” as anything ever had.

The circus wasn’t the point: the point was—as it always is— all within.

Selina, JH, Mangesh

Letter from the Kumbha Mela

As published on Yoga City NYC

Thousands and thousands of people crossing makeshift pontoon bridges over the Ganges river became a familiar sight during my 10 day visit to Allahabad, India

The men carried walking sticks or pushed bicycles, while many women, dressed in dazzling saris, lead small children or elderly relatives. They walked in silence with a steady, quiet focus, their belongings bundled on their heads and backs because they were headed to the Kumbha Mela.

While there are small Melas every year throughout India, the one near Allahabad, where the Ganges, Yamuna and mythical Saraswati rivers meet, is the most important and the most auspicious. This grand gathering happens only once every 12 years, with a Maha—or great— Kumbha Mela every 144 years (the last one was 2001).

And of course, it is the largest. When I arrived, staying on the campus of theHimalayan Institute about a mile downstream from the main site, a million people had already taken up residence.

More problematic, it’s also the loudest, with countless PA systems blasting mantras, lectures, and “swa-has” for miles around, at all hours of the day and night. I got used to falling asleep to two or three of them chanting at top volume and completely at cross-purposes.

The incessant din added a very real challenge to my daily meditation practice. The banks of the Ganges were very noisy. Numbers swelled again on the auspicious bathing day of February 10th, that coincided with the new moon, a time of new beginnings.

In one day, 10 million people flooded the grounds. Over the month or so of the Mela, 100 million people were expected to visit, living in the makeshift tentcamps, or curled up at the side of the dusty dirt tracks, running shops, serving food to wandering sadhus, and policing the 8 square kilometer area.

For such an enormous “pop-up city” it was impressively peaceful. Saints, families, villagers poor and rich mingled. We never felt in danger, even in such huge throngs. In fact, our biggest hassle was Indian pilgrims taking photos of us Westerners, and even that was done in a very friendly way.

I had come to experience the energies of the crowds and the practices of the sages. But as I reckoned with my jet lag, the noise of the fair, and the exhaustingly huge gathering of people, I wondered what everyone was really coming for, and what it means to be a pilgrim.

Kumbha means “pot” and “mela” means fair: the story is that the demi gods, running out of the elixir of happiness, or amrit, joined with their enemies, the water demons, to churn the ocean and produce more of the heavenly nectar.

But when the nectar at last rose from the sea, the gods stole the amrit for themselves alone. A battle ensued until Vishnu intervened, whisking the valuable pot of nectar away. It took 12 days for Vishnu to escape—hence the 12 year lapse between Melas—hotly pursued by both angry parties.

The pilgrims crossing into the Kumbha Mela grounds were not concerned to hear the myth again—they already knew it. They might seek out a sage or take in a dance performance; but their main purpose was to bathe in the Ganges and be purified by her inexhaustible living waters.

And not just anywhere, but as close as possible to the Sangam—the confluence of three holy rivers, where auspicious energy is most concentrated at this time.

The Ganges, the mother and spiritual source, could not only wash away transgressions and karmic impediments, but also replenish the divine grace in our lives. The Yamuna river, representing worldly prosperity, helps to keep our home, work, and social lives to progress harmoniously.

Lastly, the mythical Saraswati river, important in Vedic times, but since disappeared underground, represents the fortification of intuition and inner knowledge.

In other words, to bathe at the Sangam was like getting an extremely powerful recharge.

For Westerners, the massive number of people was undeniably exciting. Some in our group braved the highly toxic E. coli levels and dipped themselves in theSangam. Others just dipped their mala beads or sprinkled some of the holy water over their heads.

But the moment of highest spiritual buzz for me came outside of the official Melagrounds. On February 10th, the auspicious bathing day, senior teachers at the Himalayan Institute conducted a fire ceremony on campus, repeating a Durgamantra to help mitigate the fear and anger in ourselves—and in the world.

As we offered the samagri—the offering—to the sacred fire we chanted together in common purpose, propitiating the forces of transformation and new growth, planting seeds of change. It was not an empty ritual; I could feel the energy we were creating.

One important element of meditation or spiritual practice is trustful surrender to the mysterious forces at work in our world. And feeling that palpably around me was worth all the effort of getting to India, the disturbance of the loud nights, the hot, dusty and exhausting Mela, and my initial bewilderment over what it meant to be a pilgrim. I felt fortified, and that, I believe, was the whole point.

As published on Yoga City NYC

Om Trend: Wisdom Warriors

Wednesday at 1 p.m. is a hot time slot at Yoga Del Mar studio in La Jolla, California. The two-hour class features rocking music and regularly packs in 30-plus people.

But don’t try getting in if you’re under 50: Wisdom Warriors is a class exclusively for older yogis. Created by teacher Desirée Rumbaugh, 53, the class, which regularly includes advanced poses like Full Wheel and Peacock Pose, offers encouragement and support for yogis who want to maintain an advanced practice in their 50s and 60s.

“When you’re in a class with people your own age, there’s no excuse not to work hard,” she says. “It’s motivational.” Wisdom Warriors’ students say they enjoy the cama-raderie of their peers, as well as that little push to keep their practice lively. As one 60-year-old student remarked, “This is reig-niting my pilot light!”

Leaving Rio: Why I Had to Go

AS PUBLISHED IN YOGA NATION

Now that my time in Rio is coming to an end people are asking me whether I really want to go. “Don’t you want to stay longer? Overstay your visa! You could teach English!”

It’s been 2 ½ months—June, July, and half of August. I’ve lived in two apartments in the colonial neighborhood of Santa Teresa perched on a steep, cobblestoned hill in Rio de Janeiro. I also traveled in the Amazon for three weeks. Many people would not want the adventure to end. But I do.

I came to Brazil to change my perspective. I knew I couldn’t do it if I stayed in New York. I needed to know that life was more than just work. After fifteen years of surviving in the Big Apple, many of my ideas about well-being revolved around working. But my life, organized to the minute — so that I could include personal projects and a social life, as well as my job as an editor — has been feeling wrong for some time. It felt like I’d gotten off at the wrong station. It was time to get on a different train.

View from Santa Teresa over downtown to Guanabara Bay

I knew Brazil—especially Rio—could help me with this. The most important thing in Rio is one’s connections to other people; it’s about having fun (with people) and enjoying life (with other people). It’s definitely not about work. Sunday nights are bigger party nights than Saturdays: people celebrate hard on their last free night before Monday. And, while people seemed to be constantly hustling up work, no one I met in Rio had a steady job.

Brazil is famous for being the land of alegria. Nothing is a problem. Don’t have a friend? No problem: go to the corner bar and within the hour you’ll have a few. They’ll make your evening fun, they’ll invite you to eat at their house, and when you meet on the street afterwards they’ll greet you with impossibly warm and open smiles. You’ll feel like family.

Don’t know your way around the city? No problem. Cariocas will instruct you on the best places to go and anyone overhearing the conversation will give their opinions. Can’t speak Portuguese? No problem. People will band together to communicate with you. No stress! Don’t worry!

This “no stress” attitude means that plans are unnecessary. Three hours late for a dinner party? No problem. Forget to call your friends? No problem. Stuck in traffic? No problem. Land of happiness, land of alegria. I even saw a woman walking down my street with a T-shirt that said “NO stress” (in English) yesterday.

I just met this guy

And once you connect with people the warmth is genuine. Brazilians will stick around to help you solve whatever problem you’re having (bus didn’t stop for you, can’t find a street, don’t understand something etc). They will lend you money no questions asked, give you a ride far out of their way, make you food at any time of the day or night, let you cut in line.

In fact, friends of friends will be assigned to pick you up at the airport or entertain you for an afternoon if your one friend in Brazil is not available. They don’t mind extending this exceptional hospitality. Most Americans (and Canadians) would find it absurd and imposing; they would resent it.. But Brazilians like it. They become instant family. And they remember you like a dear friend. Next time they see you, they will give you a warm kiss on each cheek and stop whatever they are doing to speak few tender words. There’s never a rush. They’re never too busy to talk.

This (along with the music, the dance, and the hilarious commentary on day-to-day life) is what Brazil does exceptionally well. And it’s this I wanted more of. Brazil has helped open me up to a whole different way of living, with more ginga (swing in your game), more sensuality (I like the extra bum exposure on the beach, and the men’s bikini, the sunga) and a less Puritan morality. More alegria, less worry. As a chronic worrier, all this has helped me a lot over time.

But there’s another side to this wonderful carinho (tender warmth). And it’s this other side that really bothered me this time in Brazil. The other side of alegria is tristeza—sadness—and there is plenty of crying going on in Brazil, especially in Rio. For good reason, because things aren’t safe, there’s very little accountability (from organizations or individuals), and when things go wrong there’s no recourse.

You have to apply a jeito—a work-around—to deal with the multiple maddening problems that come up in a day, for issues as small as buying a certain kind of hook to hang your hammock to rather larger ones like what to do when your house is on fire.

Here’s a minor but good example: when my Carioca friend discovered a match-stick in his feijão (stewed black beans) he didn’t complain to the waiter. What was the point? he said, it wouldn’t change anything. He had lived in New York for ten years and knew what I was thinking. But he did make a little chorinho—a little sob story—for extra beans. And the waiter brought them, kindly, as if he was doing Daniel a personal favor. In Brazil, you have to know how to play the game.

Daniel, philosophical after finding a match in his feijao

I didn’t realize when I went to Brazil how profoundly this particular tristezais a part of the culture. I didn’t realize how deep it ran. This tristeza is erratic by nature and so it put me up against my own need for order. The casual attitude towards important things put me up against my tendency to worry, and the general lack of accountability made me scared for my day-to-day safety. I found it hard to roll with things— to be enrolando, “in the rolling,” as Cariocas are—even after a couple of months in Brazil.

I felt this keenly on my last day in Rio when I finally went up the PãoD’Acúcar, the Sugarloaf, a 1,300 foot rock accessed by a cable car that can take 65 people at a time up to a spectacular viewing area.

The thing I really noticed other than the breathtaking view was that I felt safe. I wasn’t afraid that the cables would snap, that someone would fall out of the bondinho (cable car) or off the top of the rocks. It felt like a first world experience. And this was a tremendous relief. I worried about safety constantly as I walked through the city streets of Rio.

View of Rio from Sugarloaf

Most of the time in Brazil, I was not so much afraid of being robbed as I was afraid to do simple things such as walk on the sidewalk. In Santa Teresa, the sidewalk was so narrow that every few feet I had to step off into traffic. There were also unavoidable obstacles like poles in the middle of the sidewalk that had to be sidestepped, and parked cars, or mounds of uncollected garbage. (Not to mention the ever-present clumps of dog poop.)

Wires hang down at head-height

Wires hung down dangerously from telephone and power lines over the sidewalk. They dangled at head-height and were hard to see in the bright sun and the dark rain.

The traffic coming around every corner was fast, erratic, and fearless. Motorbikes avoiding the tram tracks would come within inches of the sidewalk (that you might just be about to step off to avoid a pole, for example). Buses routinely came so close that they ripped off the rear-view mirrors of parked cars. Cars played chicken with pedestrians—not out of malice, out of habit.

City buses shook so violently I was afraid I’d bite my own tongue, my teeth chattering around in my head uncontrollably. The buses clogged the streets and competed with each other for degrees of recklessness. One driver told a friend who got on with her 5-year old daughter to hold on—and before he had even closed the door, the bus was careening down the cobblestones at top speed like the apocalypse was coming.

And it’s not like the roads, tracks, or cars are well-maintained. A tragic example is what happened to Santa Teresa’s beloved bonde (streetcar) last year. A charming last vestige of old-time Rio, the signature yellow, single-car train connected the various areas of the hilly, colonial neighborhood and crossed the old aqueduct down in the city proper, ending up in the beautiful Jardim Bôtanico, the city’s famous botanical gardens. On August 27, 2011, the bonde lost control on its way down to Lapa, smashing into a pole, killing the conductor and 5 passengers and injuring 51 other people.

Beloved Santa Teresa, facing Cine Santa, the adorable cinema; also see the bonde tracks, narrow sidewalks, and racing van

The extra tragic part is that it was avoidable. Everyone knew the bonde and its tracks needed maintenance. Everyone knew it was only a matter of time before something bad happened. There was a lot of talk about it. But as political discussions continued, people continued to ride, overloading the tram as usual. Nothing was done. Then— the worst thing possible happened. Now people are dead and there’s no more bonde.

So I adjust the motto of Brazil as land of alegria. I’ve come to call it land of “alegria now, chorinho later.” This lack of accountability and action, this disposition of “oh well” proves itself to be charming and relaxed in the moment, but dangerous and reckless in the long-term. Engage any Brazilian (at the corner bar, of course, that’s where things get worked out) in this subject and they will agree, nodding and saying, e uma locura, it’s a madness. (But you’ll see those same people doing the alegria thing themselves soon enough.)

Another maddening aspect of Brazilian culture is a lack of respect for other people, especially when it comes to public space. This is pretty puzzling for a culture that puts so much emphasis on relationships, family, and social ease.

But I’ve spent hours and hours walking around downtown, Centro, looking for Rio’s impressive colonial churches and in all this time ambulating, it’s been normal for Brazilians to walk out in front of me and stand exactly in my way. They don’t have to do this. Then, they refuse to move as I am trying to figure out how to get around them. This happens not with malevolence, but with absolute indifference to my presence. I see other Brazilians on the sidewalk throw out their hands and say, “Poha!” Shit! with a gesture that’s says, ‘what the hell are you doing? Can’t you see I’m here?’ Even though they probably do the same thing themselves.

Igreja de Nossa Senora da Gloria do Outeiro 1714-1729

If you go to a shop and want to buy something, you will have to make your presence known. Even if you are standing at the counter. Even if you are the only customer there. Even if there are 10 people behind the counter, you will need to say, loudly, firmly, “bom dia,” good day, and then bark your order. It doesn’t feel right. But their main objective is not to serve you. You have to remind people that in order to buy the Band-Aids, you need to give them money. And they are the only ones who can take it from you.

They are also famous for playing boom-boxes, speakers, car stereos, or telenovelas (soap operas, a national passion) so loud that you can’t think straight, and they’ll do it right into their neighbor’s houses without a second thought to how it’s affecting anyone else. It’s enough to make otherwise patient adults—not to mention parents of young children—lose their minds.

But here’s the other thing: no one complains. Brazilians are so reluctant to give offense that they won’t say, “Yo, asshole, turn the motherfucking stereo off, it’s 3 a.m..” Or even, “would you mind turning down the music?”

Without protest or complaint, or even an ‘excuse me,’ Brazilians will shove and squeeze you out of the way as you are getting off airplanes, boats, buses and other forms of mass transportation. And then if anyone gets hurt in the process—if the delivery guy barrelling down the sidewalk with his huge cart overloaded with crates of beer or boxes of diapers gashes your thigh, for example, as he presses forward at a dangerous speed, or knocks over your 2-year old or your frail mother—he is terribly, terribly sorry, genuinely hurt and concerned on your behalf. It’s as if he had nothing to do with the situation.

“Alegria now, chorinho later.” Everything is in the moment, at the moment. Worry about consequences later.

my friend Arjan — just a friend

I noticed this fleeting urgency in my interactions with men. If a guy thought I was attractive, within an hour he would be trying to get me into a dark corner to make out. If I refused but gave him my info, he would inundate me with come-ons and invitations for the first few days, but if I happened to be busy right that moment (taking a Portuguese class or meeting up with another friend, for example) he would just give up. As far as I could tell, there was no such thing as a period of seduction or, even a period of dating. It was now or never; all or nothing. I found all these rituals startling, bordering on predatory, but for Cariocas they seemed normal: like if the guy didn’t try to kiss you at the end of a couple of rounds of forró (a country dance) then something was wrong.

Although the dating rituals were perplexing (I couldn’t see how anything more than a quick hook-up was possible in Rio), they were harmless. Things got scary when this lack of patience—fortitude, perseverance, or even focus— extended into services on which public safety depended.

One night, I came home from Bar do Gomes, my local and charming boteco (bar) around 1:30am and to my surprise, I saw that the house next door was on fire. Helena, the woman I was renting from, was urgently calling the fire department. Her son, Rafael, and his friends were running out into the street, trying to get into the burning house. It was under renovation and no one lived there.

The boys managed to break in and douse the fire with bottled water. Then they found a n unconscious man, a worker on the house (one who had routinely played horrible radio stations at top volume, disturbing all of us). Helena drove off to get the house’s owner.

Neighbors had spilled out into the street and started a rumor that the man had snuck into the house to kill himself. At great personal risk, the boys dragged the half-unconscious guy into the street. They shook him by his arms and legs, trying to rouse him from a smoke-induced coma.

A long time had passed without any sign of the police or fire department. It was about 40 minutes later when the police arrived—slowly, and clearly annoyed to have been roused from sleep. They sauntered over to the comatose man and yanked him up from the cobblestones where they boys had laid him. The boys rushed in to protest. The policeman, aggravated, pulled his gun.

Helena, having arrived back with the owner’s lover, appeared in the street, shouting, “Amigos de Rafael, sai da rua! Sai! Vai na casa!” Friends of Rafael get out of the street! Get back into the house!

She could see the situation spinning out of control. She’d rather that the police kill this already half-dead man than pull the trigger on one of her sons’s friends—who had gotten too involved by challenging the police. I thought I was going to witness the kind of stupid murder we all saw in the movie, “City of God,” about the out-of-control drug trade and police corruption in Rio.

the fire dept finally arrives

Meanwhile a sluggish and reluctant fire truck appeared at the end of the street. It has been almost an hour since Helena had called. The station was only 10 minutes away. The truck turned in where cars were clustered on the sidewalk. The L-shaped street had another entrance—as the firefighters must have known—very close by and it was free of parked vehicles. But instead the firefighters waited for the neighbors to move their cars, slowly, one by one.

Meanwhile the fire in the house had re-ignited and thicker, greedier flames were shooting out of the second story windows. Those of us on the street stood with our mouths agape. “E uma locura!” Said a girl next to me. “What are they doing!!??” I asked. “Nao sei,” someone said, “I don’t know.” No one knew. It was a warm night but I was shivering with anxiety. It wasn’t even my property but I felt extremely unprotected.

“And this guy, if he wanted to kill himself, why didn’t he do it some normal way, with a knife or a rope? “ said a woman standing next to me.

“He wanted to make a show,” said Helena. “Burning down someone else’s house. Incrível.” Incredible.

When the bombeiros finally got up in front of the burning house, they were in no rush to put out the fire. They didn’t try to prevent the boys from continuing to run in with their water bottles. There was not even a gesture towards crowd control. The firemen were very casual about arranging their gear. They were dressed in clothes from another era that looked like they should be in a museum.

The men slowly hooked up the hose on the truck and slowly turned on the water. But when they unspooled the hose and walked towards the burning house — the hose was too short.

Meanwhile, the ambulance that had arrived did not administer aid to the comatose man (who was now more conscious and looked drugged up). Instead, the man was handcuffed and left in the back of the police cruiser while the cops —about 10 of them—stood around and shot the shit.

I stood in the street, watching helplessly. I was shaking all over. I couldn’t sleep after the fire was out and the firefighters and the police with their suspect had departed.

However, even more suprising, the next night when I related the story to locals at Bar do Gomes, no one thought it was shocking. They looked at me blankly. It was as if I had a problem. Silly, gringa, I didn’t understand that this was normal.

“There is no help. If anything happens here, I am responsible for the situation, for this house, for everyone,” Helena said the next day. “If I don’t put the fire out next door, then my house gets damaged and no one will solve that for me. If there is trouble in the street, I have to deal with it. There is no security, no safety, no guarantees. This is Brazil. It’s all a big mess.”

I imagined what it must be like owning a house in Rio. It made me very tense.

(Ten days later, one of Brazil’s biggest art collectors lost his entire personal collection in an apartment fire. It took the fire department an hour to get the ladder up.)